K ch 4 Consciousness and Transcendence; Principles of Psychology ch IX The Stream of Thought

1. Tragedies that befell him in his 40s led to James's quest for ___.

2. What experience led James to "the taste of the intolerable mysteriousness" of existence?

3. What did James think is sacrificed when we study the mind in objective analytic terms?

4. What did Thoreau say at the end of Walden?

5. His experiments with nitrous oxide gave James what warning?

6. What did James say about his house in Chocorua?

(below)

7. What does James mean by "continuous," when he says consciousness is continuous?

8. What metaphors most naturally describe consciousness?

9. We all split the universe into what two great halves?

Discussion Questions

- What does "transcendence" mean to you?

- Do you think you could remain hopeful and happy after losing a child?

- Will we ever fully understand the origins and nature of consciousness?

- Does your internal life feel continuous to you, or "chopped into bits"?

- What does being "woke" mean to you?

- Does the thought that "this too shall pass" console or comfort you? 104

- Have you read Michael Pollan's How to Change Your Mind? COMMENTS? 115

- Was Leonard Cohen right about "the crack in everything"? 116

- Do you agree with Kaag about Wittgenstein? 124

THE STREAM OF THOUGHT.

We now begin our study of the mind from within. Most books start with sensations, as the simplest mental facts, and proceed synthetically, constructing each higher stage from those below it. But this is abandoning the empirical method of investigation. No one ever had a simple sensation by itself. Consciousness, from our natal day, is of a teeming multiplicity of objects and relations, and what we call simple sensations are results of discriminative attention, pushed often to a very high degree. It is astonishing what havoc is wrought in psychology by admitting at the outset apparently innocent suppositions, that nevertheless contain a flaw. The bad consequences develop themselves later on, and are irremediable, being woven through the whole texture of the work. The notion that sensations, being the simplest things, are the first things to take up in psychology is one of these suppositions. The only thing which psychology has a right to postulate at the outset is the fact of thinking itself, and that must first be taken up and analyzed. If sensations then prove to be amongst the elements of the thinking, we shall be no worse off as respects them than if we had taken them for granted at the start.

The first fact for us, then, as psychologists, is that thinking of some sort goes on. I use the word thinking, in accordance with what was said on p. 186, for every form of consciousness indiscriminately. If we could say in English 'it thinks,' as we say 'it rains 'or 'it blows,' we should be[Pg 225] stating the fact most simply and with the minimum of assumption. As we cannot, we must simply say that thought goes on...

I can only define 'continuous' as that which is without breach, crack, or division. I have already said that the breach from one mind to another is perhaps the greatest breach in nature. The only breaches that can well be conceived to occur within the limits of a single mind would either be interruptions, time-gaps during which the consciousness went out altogether to come into existence again at a later moment; or they would be breaks in the quality, or content, of the thought, so abrupt that the segment that followed had no connection whatever with the one that went before. The proposition that within each personal consciousness thought feels continuous, means two things:

1. That even where there is a time-gap the consciousness after it feels as if it belonged together with the consciousness before it, as another part of the same self;

2. That the changes from one moment to another in the quality of the consciousness are never absolutely abrupt.

The case of the time-gaps, as the simplest, shall be taken first. And first of all a word about time-gaps of which the consciousness may not be itself aware.

On page 200 we saw that such time-gaps existed, and that they might be more numerous than is usually supposed. If the consciousness is not aware of them, it cannot feel them as interruptions. In the unconsciousness produced by nitrous oxide and other anæsthetics, in that of epilepsy and fainting, the broken edges of the sentient life may[Pg 238] meet and merge over the gap, much as the feelings of space of the opposite margins of the 'blind spot' meet and merge over that objective interruption to the sensitiveness of the eye. Such consciousness as this, whatever it be for the onlooking psychologist, is for itself unbroken. It feels unbroken; a waking day of it is sensibly a unit as long as that day lasts, in the sense in which the hours themselves are units, as having all their parts next each other, with no intrusive alien substance between. To expect the consciousness to feel the interruptions of its objective continuity as gaps, would be like expecting the eye to feel a gap of silence because it does not hear, or the ear to feel a gap of darkness because it does not see. So much for the gaps that are unfelt.

With the felt gaps the case is different. On waking from sleep, we usually know that we have been unconscious, and we often have an accurate judgment of how long. The judgment here is certainly an inference from sensible signs, and its ease is due to long practice in the particular field.[225] The result of it, however, is that the consciousness is, for itself, not what it was in the former case, but interrupted and discontinuous, in the mere sense of the words. But in the other sense of continuity, the sense of the parts being inwardly connected and belonging together because they are parts of a common whole, the consciousness remains sensibly continuous and one. What now is the common whole? The natural name for it is myself, I, or me.

When Paul and Peter wake up in the same bed, and recognize that they have been asleep, each one of them mentally reaches back and makes connection with but one of the two streams of thought which were broken by the sleeping hours. As the current of an electrode buried in the ground unerringly finds its way to its own similarly buried mate, across no matter how much intervening earth; so Peter's present instantly finds out Peter's past, and never by mistake knits itself on to that of Paul. Paul's thought in turn is as little liable to go astray. The past thought of Peter is appropriated by the present Peter alone. He may[Pg 239] have a knowledge, and a correct one too, of what Paul's last drowsy states of mind were as he sank into sleep, but it is an entirely different sort of knowledge from that which he has of his own last states. He remembers his own states, whilst he only conceives Paul's. Remembrance is like direct feeling; its object is suffused with a warmth and intimacy to which no object of mere conception ever attains. This quality of warmth and intimacy and immediacy is what Peter's present thought also possesses for itself. So sure as this present is me, is mine, it says, so sure is anything else that comes with the same warmth and intimacy and immediacy, me and mine. What the qualities called warmth and intimacy may in themselves be will have to be matter for future consideration. But whatever past feelings appear with those qualities must be admitted to receive the greeting of the present mental state, to be owned by it, and accepted as belonging together with it in a common self. This community of self is what the time-gap cannot break in twain, and is why a present thought, although not ignorant of the time-gap, can still regard itself as continuous with certain chosen portions of the past.

Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as 'chain' or 'train' do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A 'river' or a 'stream' are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life...

the mind is at every stage a theatre of simultaneous possibilities. Consciousness consists in the comparison of these with each other, the selection of some, and the suppression of the rest by the reinforcing and inhibiting agency of attention. The highest and most elaborated mental products are filtered from the data chosen by the faculty next beneath, out of the mass offered by the faculty below that, which mass in turn was sifted from a still larger amount of yet simpler material, and so on. The mind, in short, works on the data it receives very much as a sculptor works on his block of stone. In a sense the statue stood there from eternity. But there were a thousand different ones beside it, and the sculptor alone is to thank for having extricated this one from the rest. Just so the world of each of us, howsoever different our several views of it may be, all lay embedded in the primordial chaos of sensations, which gave the mere matter to the thought of all of us indifferently. We may, if we like, by our reasonings unwind things back to that[Pg 289] black and jointless continuity of space and moving clouds of swarming atoms which science calls the only real world. But all the while the world we feel and live in will be that which our ancestors and we, by slowly cumulative strokes of choice, have extricated out of this, like sculptors, by simply rejecting certain portions of the given stuff. Other sculptors, other statues from the same stone! Other minds, other worlds from the same monotonous and inexpressive chaos! My world is but one in a million alike embedded, alike real to those who may abstract them. How different must be the worlds in the consciousness of ant, cuttle-fish, or crab!

But in my mind and your mind the rejected portions and the selected portions of the original world-stuff are to a great extent the same. The human race as a whole largely agrees as to what it shall notice and name, and what not. And among the noticed parts we select in much the same way for accentuation and preference or subordination and dislike. There is, however, one entirely extraordinary case in which no two men ever are known to choose alike. One great splitting of the whole universe into two halves is made by each of us; and for each of us almost all of the interest attaches to one of the halves; but we all draw the line of division between them in a different place. When I say that we all call the two halves by the same; names, and that those names are 'me' and 'not-me' respectively, it will at once be seen what I mean. The altogether unique kind of interest which each human mind feels in those parts of creation which it can call me or mine may be a moral riddle, but it is a fundamental psychological fact. No mind can take the same interest in his neighbor's me as in his own. The neighbor's me falls together with all the rest of things in one foreign mass, against which his own me stands out in startling relief. Even the trodden worm, as Lotze somewhere says, contrasts his own suffering self with the whole remaining universe, though he have no clear conception either of himself or of what the universe may be. He is for me a mere part of the world;[Pg 290] for him it is I who am the mere part. Each of us dichotomizes the Kosmos in a different place.

2. What experience led James to "the taste of the intolerable mysteriousness" of existence?

ReplyDeleteThe loss of his young son Herman gave James “the taste of the intolerable mysteriousness of this thing called existence” which he could not will or habituate himself out of. He chose instead to dive deeper into this mystery and found that it could be something other than intolerable. (Kaag, p. 96-7)

3. What did James think is sacrificed when we study the mind in objective analytic terms?

The objective, analytic methods of science “forever misses the subjective sense of consciousness, the perspective of the ‘mind from within’.” In dissecting consciousness using the scientific method “the continuous flow of the mental stream is sacrificed.” (Kaag, p. 99-100)

I wonder if a way might ever be devised to somehow replicate or model subjective consciousness? Not so far... and thus, so far consciousness remains ineluctably subjective. The only way to directly encounter the stream or flow is by looking within, and in each case one and only one of us is in a position to do that.

Delete5. His experiments with nitrous oxide gave James what warning?

ReplyDeleteJames sought to test some of Blood’s experiences and conclusions over a ten-year period. He went so far as to take near fatal doses o nitrous oxide at times. In using laughing gas he felt that he had arrived at proof that “the real surpassed all formal comprehension.” Reality was more than we have thought it to be and “importantly for James, (this was) a warning against overblown philosophizing.” (Kaag, p. 115)

Right. When he said his aim was "to defend experience AGAINST philosophy" he included nitrous oxide experience. Also religious experience. But his own pluralist-pragmatic philosophy he thought more rooted in experience than in traditional philosophy as such.

DeleteThings like this don't make any sense to me. All we can ever know about life is based on our senses. No matter what we do we will never transcend that reality. I feel like that is a pretty obvious concept to get anyone's mind around. New experiences will never make reality anymore curtain.

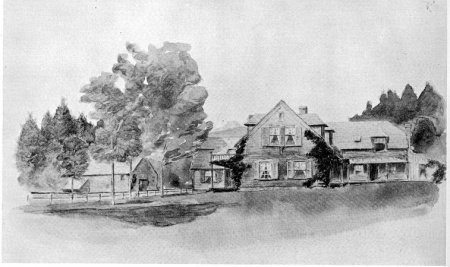

Delete6. What did James say about his house in Chocorua?

ReplyDeleteJames retreated to a newly purchased tract of land with a large house in Chocorua, New Hampshire situated in an wild setting which itself reflected the “mysteriousness of existence” and “could stretch the bounds of consciousness.” James wrote: “What I crave most…is some wild American country. It is a curious organic-feeling need…a certain proclivity for open spaces…(their house in Chocorua had) fourteen doors, all opening outwards” and James was determined to direct his study of consciousness in an outward direction. (Kaag, p. 121-2) These observations resonate with me when I recall my being drawn to my grandparents farm, camping with the Boy Scouts, exploring our Tennessee state parks interiors until I finally experience a virgin forest area. Later in life I felt drawn to National Parks, and especially to the experiences I had spending weeks in the pristine Canadian wilderness (Quetico) where we could drink the water off our canoe paddles and often did not see another person for days at at time. I especially recall the last days of a week we spent in Quetico when we realized that there were wild fires in the park and people were being evacuated. We slept on a island our last night before paddling out of the park. We spent that night smelling smoke and hoping the fire would not jump across the lake to the island where we slept. Quetico was unfortunately completely closed due to wild fires this past season, an apparent result of global warming. These and other experiences in Quetico left me with a new grip on reality and the meaning of human life and death in the context of the vastness of creation.

This craving for a direct encounter with extra-human nature is the most emblematic strain in American philosophy, connecting James with his New England Transcendentalist predecessors Thoreau and Emerson... and resisting philosophies rooted too deeply in culture and discourse (and too little in "the open air and possibilities of nature."

DeleteDoes the thought that "this too shall pass" console or comfort you? 104

ReplyDeleteThis thought is actually extremely comforting to me. My mom is in recovery and this is a phrase they use constantly. I have probably heard my mom say this a million times throughout my life. Nonetheless, the idea that a moment of anxiety or a bad day or whatever it is will pass, makes the thing itself seem not so bad. Allowing myself to put things into perspective and realize everything has a time stamp and that I can make it through it, makes dealing with troubles a lot easier.

This phrase is cousin to something I heard Paul McCartney say about his early days with the Beatles: When they faced an uncertain or challenging situation and someone said "What are we gonna do?" they'd reassure one another that it was gonna be okay, that "something will happen." It's true. Moments pass, something else happens. Constantly.

DeleteI think the whole concept is kind of frightening. People say, "this too shall pass" but really the converstion doesn't end there. What I hear them say is "this too shall pass as well as every other moment until you are eventually dead." Taking comfort from the ticking clock that ends in my nonexistents just doesn't do it for me. I think a better idea is to realise that no matter how bad what you are experiencing might be it is still apart of your life. The same life that brought you every good experience you will ever have. Plus, can't appreciate a good memory without a bad one.

DeleteIt is the same but slightly different lol.

DeleteSure wish more of you would post comments by 8 pm Monday nights...

ReplyDeleteAnd Wednesdays...

DeleteAnd come to Happy Hour. And come back, those of you who've strayed. "Come home, come home..."

DeleteDo you think you could remain hopeful and happy after losing a child?

DeleteThis is an extremely difficult question to respond to but I feel like having a challenge. As a person who doesn't have kids I really can't give a complete answer but as a hypothetical thinker I still have one nonetheless. I think the main reason people lose hope and all possible happiness after the death of a child is because they lose focus of everthing else. While taking psychology I learned that most people's hardest time in their marrage is while the children are growing up. The reason for this, from what I can tell, is that parents become more interested in being parents than being married. So I can definitely understand why when a child dies most couples don't make it. Mutual love for a common person doesn't equal a successful marriage. So, in light of this information, I hope to love my partner more than my children. Not to say I won't be heartbroken if a child of mine were to die. I just hope that it won't consume me.